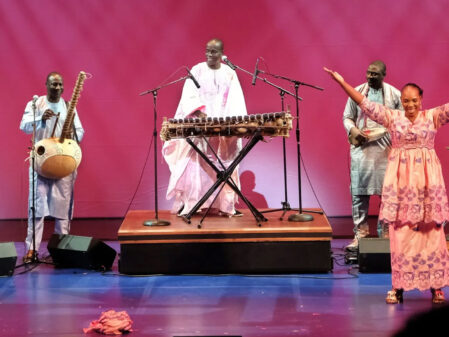

Mali Balafon Djeli | New York, NY

Balla Kouyaté was born into a musical family that goes back over 800 years to Balla Faséké, the first of an unbroken line of djelis in the Kouyaté clan. Djelis are the oral historians, musicians, and performers who keep alive and celebrate the history of the Mandé people of Mali, Guinea, and other West African countries. Balla explains that the word “Djeli” derives from his Mandinka language, “It means blood and speaks to the central role we play in our society.” One must be born into it. The Kouyaté family is regarded as the original praise-singers of the Malinké people, one of the ethnic groups found across much of West Africa. Oral tradition holds that when the emperor Sundiata overthrew Soumaora Kante, he appointed the Kouyaté family to protect the balafon. The original musical instrument survives in Kouyaté’s father’s home village of Niagassola, which lies on the Mali-Guinea border. Considered sacred, it is kept in a special hut and rarely played in public. In 2001, the “Sosso bala” was declared a site of intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO. This powerful symbol of Mande culture is brought out once a year for ceremonial playing.

Balla Kouyaté is a djeli and virtuoso player of the balafon, the West African antecedent of the xylophone. Played with mallets, the balafon is made up of wooden slats of varying lengths. Underneath, two rows of calabash gourds serve as natural amplifiers. Balla often plays on two sets of balafons, which allow him to get a chromatic scale. Although his instruments are from Mali, Balla has built the base for them. Tuning the instrument involves adding or taking away wood; to flatten a note, he planes away wood from the underside, and to sharpen the pitch, he cuts an angle. Each resonating gourd has a hole cut in it, which is covered with thin plastic. Balla notes that in Mali, they used to scoop up spider webs and place them over the small hole in the gourd. It acts as a membrane that is porous. String has replaced the use of antelope skin to tie the resonating gourds in place.

Although in Mali, it is typical for members of the current generation of Balla Kouyaté’s extended family to know how to play the balafon, Balla is the only one who has made playing the balafon his occupational profession. In addition to fulfilling the role of djeli, traditional musicians are finding increasing commercial success as soloists and band leaders. Often billed as fusion, the music explores jazz and other outside influences, while remaining consciously rooted in the Mandé tradition.

“In my culture, music is used primarily to encourage people.” True to his word, Kouyaté is ever-present performing at weddings, baptisms, and other domestic ceremonies within the West African immigrant communities of Boston, New York City, and beyond. But he is equally motivated to share his music with the larger world, driving the tradition forward. His group “World Vision” performs fusion mirroring the Afro pop music of present-day Mali and Guinea. In 2007, he released Sababu: Balla Kouyaté & World Vision. In talking about his group Balla says, “The music we are playing, the traditional music is also combined sometimes with western flavors. I believe the tradition is there; there is nothing that is going to change that. Even today, collaborating with all these big American artists, but I am still a djeli and I still do my tradition – playing at the baby shower and at the wedding, as part of my community. Nothing is going to change that, no matter how big I get.”